Let me preface by saying that I know the last four decades or so weren’t without economic hiccups — some were pretty severe, too. Still, many of the financial hardships were softened by federal safety nets, like unemployment insurance and eviction moratoriums, to help people get through major shocks, along with stimulus funds and unnaturally low interest rates to tickle growth.

As a result, we haven’t collectively experienced anything like the combination of high interest rates and high inflation that we had throughout most of the 1970s and 1980s — times that preceded when many readers of this blog were born. (If that describes you, then I’m willing to bet that your parents or grandparents remember what it was like to buy a house with double-digit interest rates.)

What happens, then, when our economic challenges are long term and more pervasive in our day-to-day lives — and the federal government is essentially out of ways to help?

As I always say, everything comes back but it comes back differently and I think we’re entering a time, economically, unlike any that most people under retirement age have ever known. What can we learn from the past without making the mistake of believing that it dictates present and future actions? (Note: There are opportunities if you read the tape, so read on.)

Bumps in the road (after a decades-long coast)

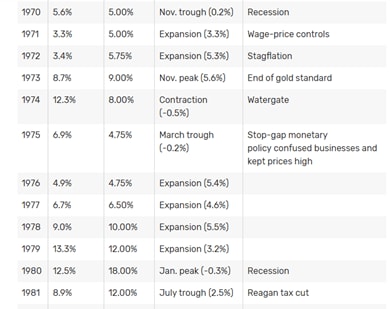

Here, I’ve excerpted two shots of

a table from The Balance to show, among other things, year-over-year inflation rates from around 1970-1980 and again, from 2008-2020. As you’ll see, from 1970-80, we lived with some pretty steep increases. And then, around 1991, we entered into a time of gentle inflation with annual rates of 3% or less that would last for three decades.

It was a feat of economic wizardry that led to phenomenal growth. On December 31, 1979, the DJIA ended the year at 838.74. On October 20, 2021, as I was drafting this

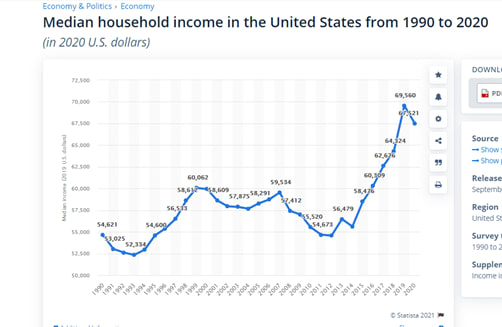

, it closed at 35,457.31. Unemployment rates overall have been low and although wages for lower-income workers are only just now budging, median incomes have at least kept pace with the rate of inflation over the last 30 years.

As a result, for the last several decades (and, clearly, economically speaking), people have known mostly good times.

We’ve been drunk on essentially non-existent interest rates for borrowing, too, and no one can really account for the multitude of ways in which

we’re (over)leveraged to the hilt. And when there have been problems, the federal government simply held interest rates low and flooded liquidity into the economy.

Stable pricing has produced growth for businesses, household income, and overall wealth and what would normally be cyclical has really been one-directional for so long that we haven’t seen hyperinflation since the 1980s and there has been optimism in the world order, hallelujah!

Now, though, I think we’re up against the wall.

One telling sign is that social security — with cost-of-living increases that have averaged about 2-3 percent each year since 1990 — is getting

an astounding 5.9% boost in 2022.

And our seniors are going to need it.

Inflation is currently projected to end 2021 at 6.1% and while many economists and analysts predict only a 3% rise in 2022 (due to supply-chain easing), I think they’re being optimistic. (On the upside, though, is that rising interest rates should give retirees and everyone else better returns on savings.)

What would the money-wise do?

As always, I won’t tell you what to invest in, but I will happily tell you what kinds of things to look for as you read the tape and make your own knowledgeable determinations about where to put your hard-earned dollars.

- It’s worthwhile to look back at the 1970s and 1980s — periods of hyperinflation and high interest — to see which industries and companies did well then and to figure out why. For example, people will always need food, medicine and energy, these are non-negotiable. Having said that, though, think about how people will eat: Which companies help Americans stretch our food dollars? Which heat our homes and fuel our cars? Which provide more fuel-efficient and affordable cars?

Concerns like this were pivotal in the 1970s and 1980s and should we see tough times ahead (as I think is likely), they will be concerns again. Here’s a look at Fortune 500’s Top 25 companies in 1981:

- Consider what’s changed since then. Technology as we know it today didn’t exist. How could it be applied now to benefit the majority of Americans? In my opinion, companies that excel in manufacturing and distribution logistics, for example, will be interesting options, because they can manage supply and costs.

- For the last three decades, we’ve gotten away from investing in products that are tied to interest rates; however, when interest rates are high, things like TIPS (Treasury inflation-protected securities) and other bonds can be safer bets with some benefits.

What would I likely avoid? Things that either aren’t necessities or commodities that can’t change pricing responsively — like high-end cosmetics (people will go back to drugstore brands when money is tight) and higher-price clothing when there are lower-priced options. (However, and as with all categories, luxury brands aren’t impacted by inflation in the same way because the wealthy don’t really feel the impacts).

Price elasticity is important, too, so businesses in highly labor-intensive industries with little room to raise consumer prices (like fast food) tend to hurt more. (One thing that could tip the scale in their favor, though, is a change brought on by the pandemic — with many restaurants limiting or dropping dine-in options, including fast food, they may be able to keep labor costs lower.)

What about residential real estate?

Typically real estate is a hedge against inflation, but if interest rates on mortgages creep up more, as I think they will, I predict several impacts on the housing market, including:

- It will reduce home-buying budgets (historically low mortgage rates were a key driver of the huge spikes in home-sale prices over the last decade).

- When budgets are reduced, it means there are fewer viable buyers per home — and, thus, home prices may tick down to expand the buyer pool.

- There will be less relocation — people who are locked in low rates won’t give those up if they don’t have to relocate for work or other concerns.

Another market indicator is

Zillow’s recent admission that it’s putting the brakes on ibuying. Sure, their explanations about too many homes and not enough contractors and supplies to update them and put them back on the market are true, but is it the whole picture? I’ve been a real estate entrepreneur for a long time and in my gut, I believe I know the answer.

Get ready now

When investors are caught off guard, that’s when losses add up. And in my opinion, although what we’re headed into isn’t going to be exactly like anything we’ve been through before, a wait-and-see outlook isn’t the best play.

It’s a good time to review portfolios, see where our collective irrational exuberance of the last several years has taken hold and make decisions about which is most important over the next several years: preserving and growing slowly but steadily or aiming for the kind of gangbusters expansion that we’ve seen?

To each their own. For me, though, I’m just old enough to remember the pain of the 1970s and 1980s, experienced enough to see the differences now and optimistic enough to find opportunities down the road.

Thanks for reading, have a great week.