For two years, life hinged on one thing: The pandemic. While that’s not quite behind us yet, today it’s the Russian invasion of Ukraine that rightly dominates the news. The situation – which leaves me both heartbroken because of Putin’s inexcusable disregard for life and inspired by the courage demonstrated by President Zelensky and the people of Ukraine – also brings with it economic impacts that may go well beyond the reach of Russia’s borders. In fact,

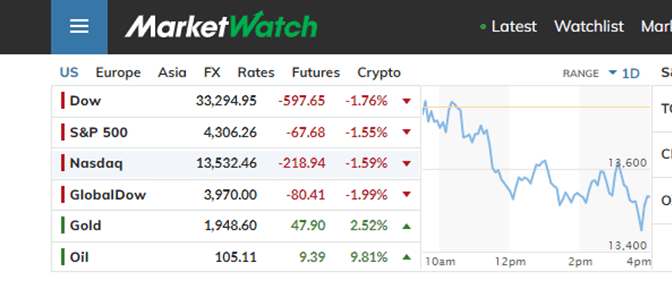

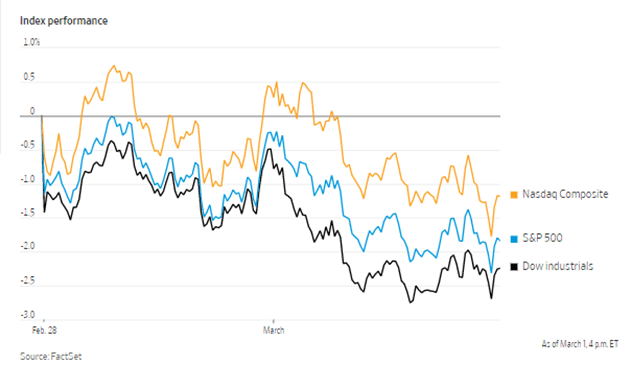

the incursion is already roiling the stock markets and we’re experiencing higher prices at the gas pumps.

No one can predict just how long this will last or how far Putin will go in his quest to reunite the Soviet Union. But certainly, the vast and deep sanctions by dozens of countries and pullbacks by a growing number of global business leaders will eventually hit home for Russian citizens.

And while Americans are incredibly fortunate if our most significant impact, overall, is economic in nature (unlike the people of Ukraine), it will still hurt. The question is, just how bad will it be?

In “

Russia is Sowing Conflict with Ukraine. What Does that Mean for the U.S. Economy?,” the

New York Times laid out the potential impacts on energy costs (in the U.S. and in Europe, the latter of which has depended on Russia for 40% of its natural gas and which had already been experiencing exorbitant increases in costs and shortages in supplies and, as of this writing, oil is up over $100/barrel); food prices (did you know that Russia is one of the world’s largest suppliers of wheat?); and essential metals. And that was before the invasion began.

Now, as inflation is already soaring in the U.S. and armed conflict will make just about everything worse, short of a swift resolution, I don’t see any way around a recession.

The hope and fear behind rate hikes

In a nutshell, when interest rates rise borrowing drops, which tends to slow spending, which means that demand for goods and services drops, which then helps to rebalance supply and demand and helps to put the brakes on inflation. The challenge, though, is to raise rates just enough so that the resulting effect is more of a slow-but-steady pressure, rather than a jolt. I bring this up now because the U.S. is already experiencing the highest inflation in 40 years and

the conflict could exacerbate this, as I pointed out in this post a couple of weeks ago.

“Because higher interest rates mean higher borrowing costs, people will eventually start spending less. The demand for goods and services will then drop, which will cause inflation to fall.

A good example of this occurred between 1980 and 1981. Inflation was at 14% and the Fed raised interest rates to 19%12. This caused a severe recession, but it did put an end to the spiraling inflation that the country was seeing. Conversely, falling interest rates can cause recessions to end. When the Fed lowers the federal funds rate, borrowing money becomes cheaper; this entices people to start spending again.

A good example of this occurred in 2002 when the Fed cut the federal funds rate to 1.25%. This greatly contributed to the economy’s 2003 recovery.”

That was last week, though – and once again, the world as we’d known it has changed.

What would I do now?

Investors are scrambling and you may be wondering what the best course to take is, too. As I always say, everything comes back, it just comes back differently, so think about where that gets us.

In times like this, the basics – housing, energy, food, transportation and utilities, for example – tend to be good options. As for stocks that soared in relation to the pandemic, while some of the companies may have the potential for good long-term growth, do some research to find out where they’re headed.

What about tech stocks? In my opinion, right now they’re still overvalued. The future rides on tech, though, so if you sense a good opportunity, do your due diligence and make your best play.

A lot of analysts favor cash in uncertain times and while I believe that it’s wise to have some on hand, I don’t recommend going too far in that direction, as inflation is too high and it’s simply too corrosive on the dollar. And although I’m not among those who flock to gold, as could be expected,

it’s rising along with each day that the incursion goes on.

“Investors pulled nearly $160 billion from money-market funds and $17.5 billion from bond mutual funds and exchange-traded funds in the first seven weeks of the year, according to Refinitiv Lipper. The exodus is already on pace to be the biggest in at least seven years.

About $50 billion was funneled into stock funds over that period, including nearly $21 billion so far this month.

The massive reshuffling of assets comes in the midst of a changing economic and monetary landscape. Worries about surging inflation and the Federal Reserve’s plan to

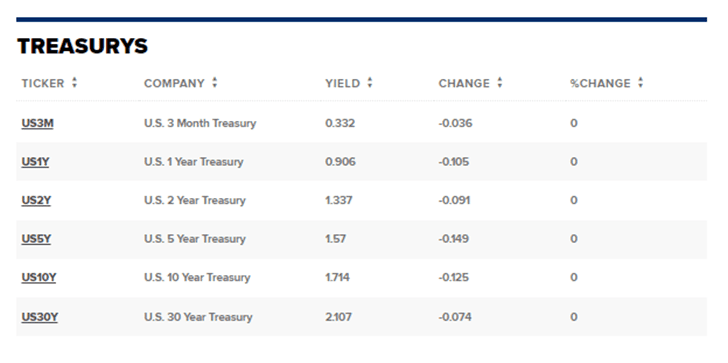

begin raising interest rates as soon as next month has put the bond and

stock markets under pressure to start the year.”

As I write this (on March 1), CNBC reports, “The Russian invasion of Ukraine has entered its sixth day. The attack has roiled global markets and seen investors look to safe-haven investments like U.S. government bonds, pushing yields down.”

As far as real estate goes, residential real estate is always an inflationary hedge but you have to keep in mind the bigger picture, too, because it’s also overvalued and inflation can mask real values and real returns: If your home’s value goes up by 3% this year but, at the same time, inflation hits the projected 7% this year, that’s an overall decline in value. For example, if your home value rises to $103,000 from $100,000 (a 3% increase), but inflation is factored in, the real value is closer to $95,790. That means that not only is it worth less than you thought, but you’d need the real value to rise even more – by about 7.6% vs. 7% – to get back to $103,000.

That’s why real estate will work in your favor as an inflationary hedge over the long run, but not in the short term during periods of high inflation.

And right now, simply sitting on the sidelines until things settle down is a fine option, too.